“Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”[1] is recognized as the original definition of sustainable development. That concept was eventually stated in terms that resonated with the general public as the “triple bottom line.”[2] Since then, the phrase “people, planet, and profit” has focused attention on making decisions with more than Milton Friedman’s “maximizing shareholder profit” sole criterion in mind.[3] Today, a common expression of organizational sustainability is the equal consideration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors in decision-making.

Frameworks for incorporating metrics of sustainability into organizational decision-making started to emerge as early as 2000 when the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) published its first reporting guidelines. Over the last 20 years, numerous approaches to measuring sustainability and reporting have emerged.[4] Today, more than 80% of Fortune 500 companies are issuing voluntary annual reports to document their progress toward sustainability metrics.[5] While private corporations set goals and monitor ESG metrics, public sector organizations are taking action to become more sustainable. City mayors have made commitments to mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by honoring the Paris Agreement. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) notes that “proactively implementing the policies and actions identified in your mitigation plan increases community resilience and is an investment in your community’s future safety and sustainability.”[6] At the federal level, an Office of Federal Sustainability has been in place since 1993 while the General Services Administration is “proving every day that healthy and productive workplaces, a smaller environmental footprint, and reduced costs go hand-in-hand” (for example, see here).

Environmental Sustainability in Practice

Here are some examples of how manufacturing, mining, oil & gas, power, public sector, real estate, and solid waste organizations are addressing environmental sustainability.

Manufacturing

Beginning in 2010, many manufacturers were required by the U.S. EPA to quantify their GHG emissions for the first time.[7] As stakeholders have demonstrated a desire to understand the carbon footprints of the companies in which they invest, corporations have expanded their reporting beyond their direct (commonly called Scope 1) emissions.[8] Today, it is common for manufacturers to not only comply with mandatory GHG reporting but also voluntarily report their upstream and downstream GHG emissions to third-party entities such as CDP, which is a not-for-profit organization that manages a global environmental disclosure system.

Mining

According to a KPGM survey, 80% of mining companies globally produce sustainability reports.[9] High on the list of environmental concerns for the industry is water stewardship. Climate-related changes in rainfall intensity and frequency may lead to physical risks associated with either too much or too little rainfall. Extreme storms may pose risks to earthen dams/embankments, tailings storage facilities, and landslides. Chronic dry spells may reduce water availability for processing. These acute and chronic risks have become integral to planning in the mining industry.

Oil & Gas

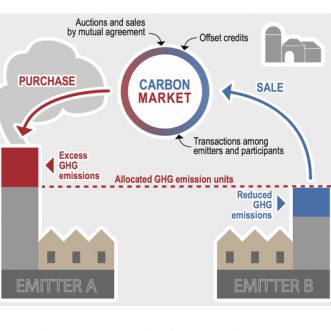

There has been a lot of talk in the energy sector recently about corporate pledges to achieve net zero emissions by certain future dates; prominent examples include Range Resources (2025), Dominion Energy (2050), and BP (2050). In general, these commitments indicate the intent to reduce GHG emissions associated with the production of their products and the offsetting of those emissions that cannot be reduced. Decarbonization will involve a wide range of solutions, including improvements in energy efficiency and greater use of renewable energy. Offset programs such as afforestation and reforestation initiatives aimed at sequestering equivalent amounts of emitted carbon and technological measures aimed at the capture of fugitive methane have been in use for over a decade.[10]

Power

“Companies in the electric power industry are facing increased demands from investors and other stakeholders about how they are incorporating climate risks into their investment decisions and overall business strategies,” according to Ceres’ 2018 framework, Climate Strategy Assessments for the U.S. Electric Power Industry. Coincident with the expansion of natural gas as a power generation fuel have come investor-led evaluations of potential societal and physical risks associated with climate change. Investments in projects that would produce large quantities of GHG are now being evaluated relative to their climate change risks as an element of project financing evaluations.[11] While the power sector has been on the leading edge of vulnerability assessments associated with physical risks such as coastal storms, societal risks such as regulatory and market changes are now being included.

Public Sector

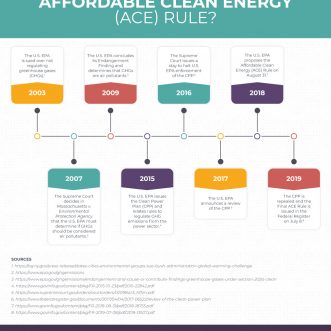

According to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES), 32 states have or will soon release a Climate Action Plan. These plans assess vulnerabilities, risks, and potential impacts and then present strategies and actions to help mitigate impacts, improve resilience, and promote adaptation to change. Such plans dovetail with the Hazard Mitigation Plans (HMPs) that state, local, and tribal jurisdictions prepare to be eligible for Stafford Act funding.[12] HMPs are now required to include “new hazard data, such as recent events, current probability data, loss estimation models, or new flood studies…and consideration of changing environmental of climate conditions that may affect and influence the long-term vulnerability from hazards in the state.”[13] As of 2019, the majority of state HMPs had incorporated climate change into their planning process.[14]

Real Estate

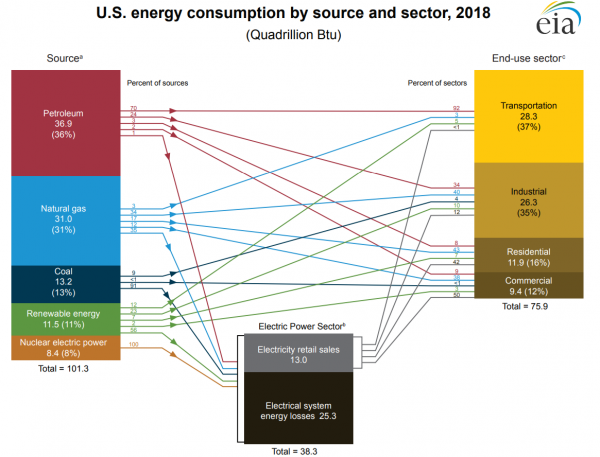

The real estate sector has a long history of designing and implementing sustainable solutions. The U.S. Energy Information Administration currently estimates that residential and commercial sectors use about 28% of all U.S. consumed energy. Building energy code programs in combination with private-sector rating systems such as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) have helped conserve energy. As corporations aim for net zero GHG emissions, energy conservation and renewable energy strategies will continue to be key strategies in their plans.

Solid Waste

Renewable natural gas (RNG) is the industry term for methane that has been separated from the landfill gas (LFG) that is produced by decomposition of solid waste in landfills. As of August 2020, there were about 565 operational LFG projects in the U.S. Most of these projects are generating electricity while others either use the gas directly or deliver it to a pipeline. The U.S. EPA estimates that some 475 additional landfills are good candidates for LFG projects. Meanwhile, more and more landfills are finding that the expansive surface of a closed landfill is ideal for the siting of solar photovoltaic arrays.

Summary

These examples highlight some ways private and public organizations are focusing attention on environmental sustainability. Equally important are the societal and governance aspects. Depending on how an organization assesses the importance of issues to its stakeholders, societal or governance actions may be prioritized over environmental actions. As the nation struggles with the ongoing pandemic and social inequities, communities and businesses are evaluating how sustainable their organizations really are and what actions can be taken to increase their resilience.

For more information about any of these topics or questions about how CEC can support your sustainability initiatives, please contact Kris Macoskey (412-249-3147; kmacoskey@cecinc.com).

Footnotes

[1] Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future, UN Bruntland Commission (United Nations, 1987).

[2] Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business, New Society Publishers (Elkington, 1998).

[3] The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits, The New York Times Magazine (Friedman, 1970). See also Greed is Good. Except When It’s Bad, The New York Times Magazine (September 13, 2020) for a 50-year look back at Friedman’s landmark thesis.

[4] See Ram Ramanan’s Introduction to Sustainability Analytics (CRC Press, 2018) for an excellent overview.

[5] Corporate Sustainability Reporting: Past, Present, Future (U.S. Chamber of Commerce, 2018).

[6] Local Mitigation Planning Handbook, FEMA, March 2013, p. 9-6.

[7] Mandatory Greenhouse Gas Reporting, 40 CFR 98.

[8] Scope 1 refers to emissions produced by the facility as are commonly reported to the U.S. EPA under 40 CFR 98. Scope 2 refers to the GHG produced by purchased electricity. Scope 3 captures upstream and downstream GHG emissions sources within prescribed assessment boundaries such as employee commuting, product deliveries, or leased assets.

[9] The Road Ahead—The KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2017 (KPMG, 2017).

[10] See the American Carbon Registry for examples of offset strategies.

[11] See The Equator Principles (July 2020) and Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (June 2017).

[12] See 44 CFR 201 – Mitigation Planning for more about the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act.

[13] State Mitigation Plan Review Guide, FP 3-2-094-2 (March 2015, FEMA).

[14] State Hazard Mitigation Plans & Climate Change: Rating the States 2019 Update, Columbia Law School Sabin Center for Climate Change Law (Adler and Gosliner, 2019).

Post a Comment